Were reliability studies a new discipline for Elf?

Not exactly, for example, studies had already been carried out for the northeast sector of the Grondin field (Gabon) in 1975. And when I started at Elf, we had two teams with six or seven reliability specialists, whose work was divided between processes and research. The Safety and Production Departments conducted their own independent reliability analyses, sometimes on the same systems. This type of organization had its limits because different results could be obtained from the same study subjects, but they would not address the same aspects (for example, safety versus availability).

During this period, a series of industrial accidents had left their mark on the public conscious and the industry (in particular, the Piper Alpha explosion in Scotland, the Macondo explosion in the Gulf of Mexico and the sinking of the Prestige in France). Reliability analyses have gradually become a fundamental part of risk management at production facilities.

As time went on and following several restructuring operations where teams were merged and colleagues retired, I found myself managing most of the day-to-day business, before hiring some young recruits who are still working today, after my own retirement in 2009.

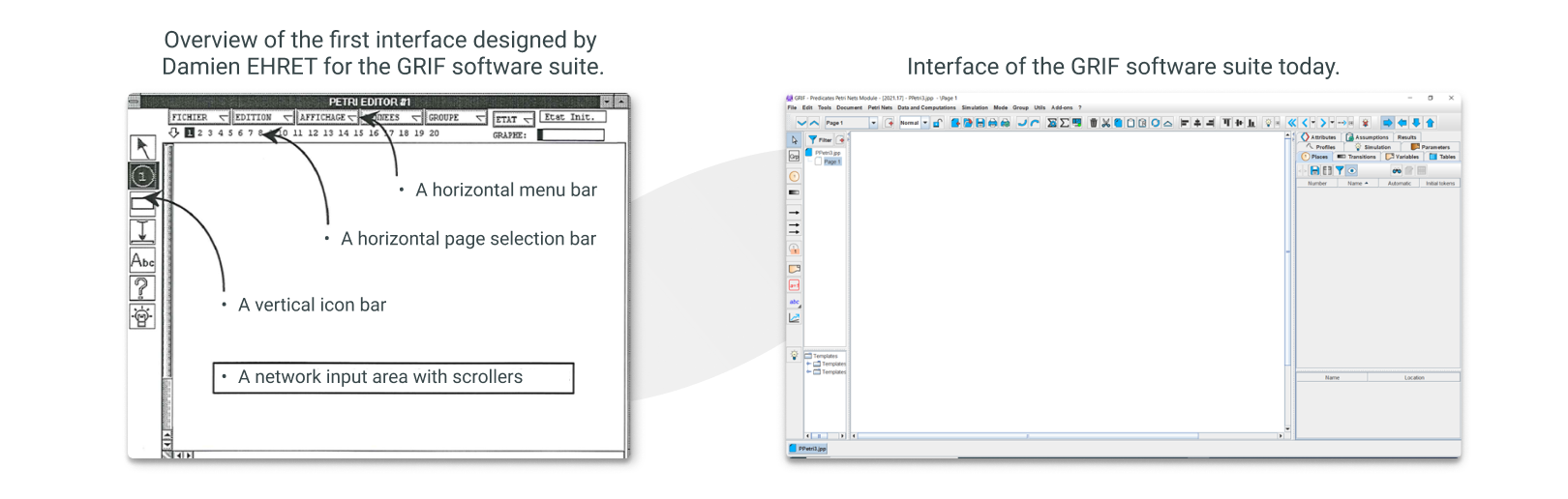

How did you conduct reliability studies in the 1980s?

Mostly by writing out all our formulas and calculations on paper! Everything was done by hand. I developed the fault trees in the form of a binary structure (outlined by René-Louis Vallée in his treatise on binary analysis), to geometrically extract the possible failure scenarios. It was hard going but it worked!

Qualitative methods relied on the “engineer’s judgment”: using the intuition, skills and experience of individuals, as well as feedback from the field, to establish the different possible scenarios (breakdowns, accidents, maintenance, etc.). As a result, we began using inductive methods such as the HAZOP (Hazard Operability Studies) method taken from the chemical industry, to determine the effect of physical parameter drifts on breakdown eventuality, and deductive methods, such as fault trees, to identify the accident/incident scenarios most likely to occur.